All the eggs in one basket: What if all of the major handball clubs scattered to the 4 corners of the U.S. were instead focused in one metropolitan area?

Would the U.S. be wise to develop a very focused development strategy around one metropolitan area? In part 1, I lay out the arguments for doing so and review historical efforts to spark development regionally. Part 2 will focus on the pros/cons, costs, risks and timing for doing so.

Iceland: 1,000 Times Smaller

Ever since I had the opportunity to play against Iceland at the 1993 World Championships I’ve been a little bit fascinated with Iceland and it’s national handball program. I even remember getting out my world almanac (yeah, this is a little bit before widespread internet and Wikipedia) because I was asking myself, “How many people live there, anyway?” Not sure what it was 22 years ago, but the current population is roughly 323,000 people. Coincidently, the population of the U.S. is approximately 323,000,000. This disparity inevitably leads to the question: How does a country roughly 1/1,000th the size of the U.S. kick our butts in handball?

Obviously, in terms of handball national team performance, there’s a lot more at play than total population. And, the key difference is that a significant portion of Iceland’s very small population is very focused on handball, whereas in the U.S. a very miniscule percentage has the same dedication. Seriously, depending on how you want to define it, it’s really small. I would argue that there are only around 300 really dedicated handball followers or around 1/1 millionth of the U.S. population. Bump it up to a 1,000 if you want, but you’re still talking about 1/300,000th of the U.S. population.

Creating a Little Reykjavik

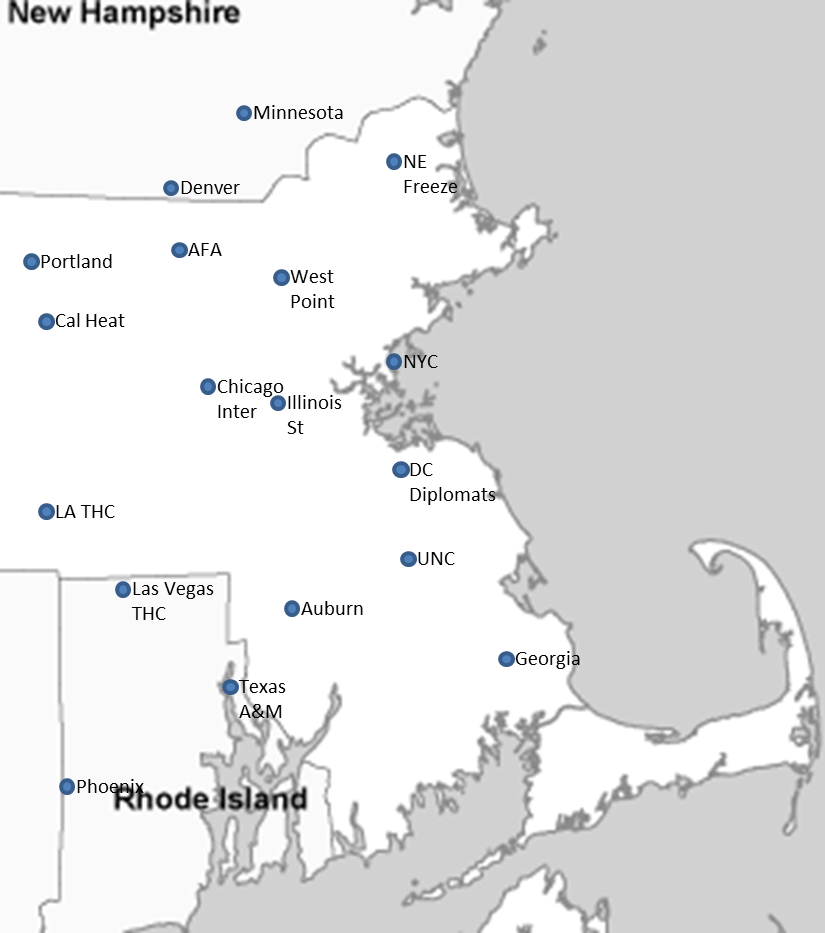

Compounding the U.S. struggle is the reality that the handful of folks that really care about the sport are scattered throughout a huge nation, making it a struggle to work together to grow the sport.

Over the years I’ve found myself thinking about this problem, relating it to Iceland and playing a little numbers games of population comparison. I grew up on a farm in the state of Iowa (around 10 Iceland’s) and not too long ago lived in Las Vegas (6 Iceland’s). I remember driving across town and looking over towards the sprawling suburbs next to the mountains and thinking, “Hey, I just drove past a couple of Iceland’s.” And, now I live in Colorado Springs with a metropolitan area a bit bigger than 2 Iceland’s.

As, I’ve played this little game I’ve thought about what could be done if everyone who cared about the sport of team handball lived in the same place. Be it Iowa, Las Vegas, Colorado Springs, Boston or even Auburn, Alabama. In short, I’ve asked myself:

What if we could throw all the eggs in one basket?

What if…..

- Instead of top clubs scattered throughout the country they all resided in one compact area?

- In one metro area, there were 10 top senior club teams regularly playing each other in a league competition?

- There were 20 collegiate teams feeding those programs.

- There was a Handball Development Academy training the top players in those colleges on a regular if not daily basis?

- There was a sanctioned High School sports program in that city feeding those college programs with new recruits?

- There were 50 youth clubs training and playing games, feeding the high school program?

Why, if all this were true and somehow came to pass it would be, as if, the U.S. had a little Reykjavik all its own. Or, as I like to call it the “All the Eggs in One Basket, Iceland Strategy.”

Organic Success

To some extent such a strategy has indeed been implemented to varying degrees in other sports. In most cases, though, it wasn’t actually a strategy. It just happened organically or naturally without artificial help. Case in point, are a couple of sports that for many years were essentially Californian, water polo and volleyball. Yes, there was a time not that long ago when competitive volleyball was very California centric. And, it still pretty much is when you’re talking men’s volleyball. And, although water polo has spread it’s wings some, all one has to do is look at where the bulk of the collegiate programs are to see that it is still very California centric.

The advantage to this regionalism is that the sport had critical mass in terms of local competition and development. Critical mass in that there were plenty of teams to play each other and create development at younger age levels. However, if that interest had been spread out evenly across the vast United States there would have been no critical mass. Clubs would have had to travel vast distances for competition. Isolated clubs might have sprung up, but these pockets of growth would be susceptible to periodic collapse of clubs and lack of interest. Youth teams with no one to play would struggle to even get started. Why volleyball might never have become what it is today. Water polo might even be the equivalent of what Team Handball is in this country. A non-relevant sport from coast to coast.

Non-Organic Experiments with Limited Success

But, can such a regional massing of clubs and interest be created nonorganically? Can a federation take steps to proactively create a little handball Reykjavik? The answer is yes: steps can be taken. In USA Team Handball’s case the primary tools for doing so has been national team residency programs and investment to capitalize on the Olympic host city exposure.

Since the mid 1980s residency programs have been located in Colorado Springs, CO; Philadelphia, PA; Atlanta, GA; Cortland, NY and most recently Auburn, AL. In each case the massing of athletes in one spot has had some development effect on the local area. First off, just simply practicing an unfamiliar, but cool looking sport inevitably attracts a few onlookers to try it. Some of those athletes even became national team players. The athletes based at those locations also often did community outreach to facilitate development. Finally, for a variety of personal reasons some athletes settled in the residency program location and still live there today.

Unfortunately, none of these locations have had much success in terms of sustainable impact. Today, Colorado Springs has a local club mostly comprised of aging veterans that gathers occasionally to provide competition for the AF Academy. Over the past decade or so there have also been some decent youth programs in the Colorado Springs area, but no program is currently active. To the best of my knowledge pretty much nothing exists handball wise in either Philadelphia or Cortland, NY, but neither or those locales were residency sites sufficiently long enough for any side benefits to take effect.

In terms of an Olympic boom, both Los Angeles and Atlanta clearly benefitted from the exposure that an Olympics can bring. In the case of L.A. the 1980s were clearly the high tide for the sport there. At one time there was as many as 5 clubs in the LA area and the Boys & Girls clubs had dozens of programs throughout the area. But the buzz was not sustained and by the mid 1990s there was just one club, LA THC which still exists today.

And then we have the test case of Atlanta, which benefitted from an Olympics, a Residency Program and even having the Federation HQ co-located there in the late 1990s. For a time, Atlanta was indeed the closest the U.S. has ever come to having a little Reykjavik. Atlanta had two solid clubs (ATH and the Condors), a development program with the Boys & Girls Club and the South East Team Handball Conference, the largest collegiate league the U.S. has ever had. Years later, however, there is little to show for. Gary Hines who rose up through the ranks is a mainstay on the national team, but the youth programs and ATH and the Condors are no more. All Atlanta has now is a newish club, Georgia Team Handball which has little link with the past.

What’s to be learned from these experiments? On the one hand, you could look at all of these experiments simply as failures and proof that you can’t artificially create a little Iceland. I would argue, however, that position doesn’t take into account the limited planning that went into these experiments. In LA’s case the growth that occurred was pretty organic. There was funding from the 84 Olympic Foundation, but there were also dozens of firm believers willing to put in the work. The same can be said, as well, in Atlanta. There was funding support, but there were also plenty of dedicated volunteers. Colorado Springs may be somewhat of a disappointment, but that fails to account for its smaller size. Finally, the programs in Philadelphia and Cortland never were around long enough to take root. And Cortland was also probably hampered by its smaller size and location.

So, maybe the problem wasn’t so much with the concept, but with the choice of locations and with the lack of overall planning to make it a truly focused integrated effort. Maybe the U.S. could learn from it’s past mistakes and modest successes to build a better mousetrap? In part 2, I’ll lay out what could be done with a very focused regional effort.