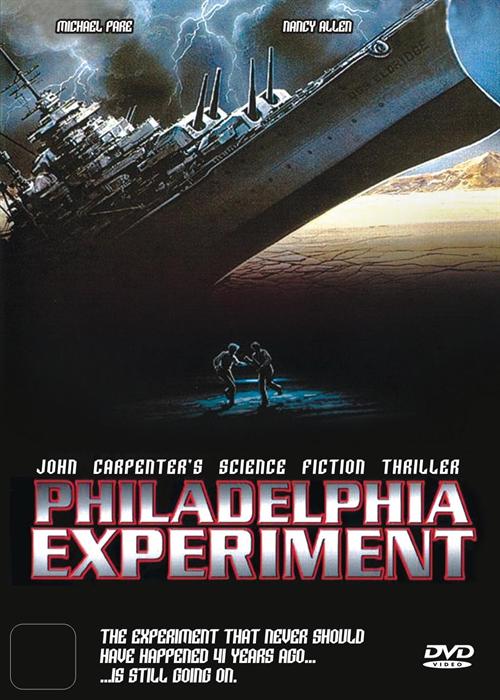

- USA Team Handball’s Strategic Planning is listing to the side; It’s time to right the ship.

The previous parts of this series (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) raised some questions in regards to USA Team Handball’s plans to establish residency programs and full time coaches. This installment sets aside the plan itself and takes a look at the planning and decision making processes that were used to develop it. And finally some suggested actions going forward.

It’s easy to critique a plan

As I’ve spent the last several parts of this series highlighting some shortcomings with USA Team Handball’s plans for its National Teams I think it’s appropriate that I also acknowledge the basic truism that it’s relatively easy to sit on the sidelines and critique a plan. This is especially true when the plan is tackling a difficult problem or objective. And trust me, as someone who’s thought quite a bit about what could be done to improve the quality of our National Teams we’re talking about an incredible challenge. Just about any plan could be picked apart by naysayers.

It’s not so easy to critique a plan developed through a structured process.

But, maybe the plan that’s been developed, while flawed is still the best plan that could be conceived. A plan that was first compared with other options and possibilities and stood out as the best option to pursue; A plan fraught with risks, but one that still makes sense to pursue; A plan that’s designed to meet the clearly articulated goals and objectives of the organization. When confronted with a plan that maps everything out, the critic can’t help but see the rationale for the course of action chosen.

What I’m alluding to here is Strategic Planning. This Wikipedia article provides an overview, but in simple terms, Strategic Planning can be described as the process of figuring out what you want to do before you go off and do it. It involves determining your goals and objectives and then assessing the feasibility of different options (tactical plans, if you will) to achieve those goals and objectives.

While this seems like an inherently obvious first step all too often it’s given short shrift by many organizations. This happens for a number of reasons. Sometimes organizations think they already know exactly what they are trying to accomplish. And, all too often it’s human nature to want to work on the solutions because it’s more concrete and tangible.

USA Team Handball’s Goals and Objectives: Do they exist?

Let’s first consider the possibility that it’s readily clear what USA Team Handball is trying to accomplish. At first blush, it’s pretty clear. Take a look at the Federation mission statement:

The mission of USA Team Handball shall be to develop, promote, educate and grow the sport of Team Handball at all levels in the United States and to enable United States athletes to achieve sustained competitive excellence to win medals in international and Olympic competition.

Just about anyone involved with the sport in the U.S. will agree with these very broad goals. But, if you start to break that one sentence down piece by piece consensus will quickly disappear. For instance, which is more important developing and promoting the sport at all levels or enabling athletes to win medals? Which part gets more resources/funding? What’s the timing involved? What are the lower level goals objectives? etc., etc. To the best of my knowledge USA Team Handball has never clearly identified lower level goals and objectives and their priority. Perhaps it’s been done at some point in the past, but I’ve never seen that sort of documentation. Instead, best that I can tell USA Team Handball has always made a beeline to implementing initiatives, activities, action plans (whatever you want to call the different things that have been tried), without spending enough time assessing whether those efforts make sense in the grand scheme of things.

This is not to intimate that those efforts were a total waste of time and resources. On the contrary, very few efforts had no value and if even if there were negligible results there usually was some rationale for trying. The question, however, is not whether an effort has value. The questions instead are how well does that effort map to goals and objectives and how does that effort fair in terms of “bang for buck” against other competing efforts. Because rest assured when the Federation makes an announcement that there is “no funding in the budget” for a National Team trip what it’s really stating is that other budget items were assessed as a higher priority.

Or, at least one hopes that such a comparative assessment was done. The troubling reality is, however, it can’t really be done without something to “grade” the effort or plans to. Without clear goals and objectives you’re flying by the seat of your pants. Deciding what efforts to pursue becomes largely intuition or even worse a yes/no on the first plans presented without an in depth exploration of other possibilities.

The way ahead for U.S. National Teams: Numerous possibilities

As a case in point, I’ll just list out some possibilities that could be considered for U.S. National Teams and player development. I won’t go into great detail. That’s not the point. The point is to just show the varying options:

– Establish regional Centers of Excellence

– Establish a European based training center in collaboration with the IHF and other developing nations

– Provide stipends for overseas training with clubs to the nation’s top 30 players

– Provide funding to 10 U.S. based clubs to support player identification and training

– Designate one metropolitan area in the U.S. for Elite competition and apply funding to make it happen

– Identify national team coaches for an extended period of time, but pay them only part time wages

– Hire a full time recruiting coordinator and have them focus on expanding the player pool at ages 18-22

– Hire a full time youth development coordinator and have them focus on developing a model program in one U.S. metropolitan area

– Work with a designated school district to implement a sanctioned High School Team Handball League to serve as a model for other school districts.

– Work with the NCAA to identify one Division 1 conference to support a Team Handball League

– Conduct a 10 day U.S. Olympic Festival style training camp for 120 elite NCAA athletes.

– Sharply curtail current expenditure on U.S. Senior teams and focus entirely on Under 21 development in hopes of improving odds for 2020 qualification

– Sharply curtail Men’s National Team funding and focus on the brighter prospects (weaker competition/Title IX) for Women’s team development .

– Sharply curtail funding and resources related to adult club teams and focus efforts on college and youth teams. (i.e., Don’t waste time organizing competition and national championships for predominantly Expat players or athletes over the ages of 25)

Could I, or anyone for that matter, poke holes in regards to the merits of any one of these possibilities? Of course. But, I could also make a case for any one of these to be the best course of action. Yep. The reality is that depending on how you interpret the Federation’s Mission Statement, you can make the case for or against any one of these possibilities.

Right Idea

To the credit of former Board Chairman, Jeff Utz, and Interim General Manager, Dave Gascon, they recognized this problem and set in motion some plans to fix it. In April of 2012 they organized a Strategic Planning Conference that was attended by around 25 individuals (Board members, USOC Reps, and assorted members of the Team Handball community at large). As someone who’s done Strategic Planning for a living and has recognized this problem for years I’ll say that the conference was a good start to solving this problem. The second day devolved way too quickly into the implementation of potential solutions, but again it’s human nature to want to work on something tangible. The good news, from my perspective at the time was that the work would continue via committees that would focus on specific topical areas. Here’s an interview with then Chairman Jeff Utz discussing the conference and here’s a list of the committees that were set up. (Editor’s note: 8 of the 10 committees that were established after the 2012 conference were removed without explanation from the Federation committees webpage sometime in 2013. This Federation news item from June 2012 lists the 10 committees and solicits additional volunteers.)

Flawed Execution

Following the conference, however, for reasons that are still unclear to me the work of the committees towards a Strategic Plan was stopped. The committees were asked to send their ideas for implementation and then lacking further guidance and direction they essentially ceased to function. At least this was the case for the 3 committees I was on: High Performance, Pipeline Development and Event Management. While I might have thought that the High Performance and Pipeline Development committees would be involved in reviewing the merits of different efforts for Board of Director consideration that simply was not the case.

Instead, several months later I read the following in this posting on the Federation webpage:

“Garcia-Cuesta and Latulippe, as volunteers, as well as Gascon, and Technical Director Mariusz Wartalowicz, have collectively developed a long-term strategy for the development of the USATH High Performance Program which focuses on the recruitment, training, development, and elevating the stature of our National Teams.”

Is it lost on anyone that two former National Team coaches that coached U.S. Residency teams were part in parcel to the development of a strategy that calls for hiring National Team coaches and establishes residency teams? Strikingly, this reminds me quite a bit of the Vice-Presidential Selection Committee that Dick Cheney conducted for George Bush.

Setting all sarcasm aside, however, it’s really not that surprising that they went with what they know and one would hope, anyway, an improved version of what they know adapted to current realities. And for all I know those four gentlemen might actually have spent countless hours reviewing dozens of possibilities, carefully analyzing their pros and cons and presented a full up report consisting of multiple options for the Board’s consideration. (i.e., the kind of work a High Performance or Pipeline Development committee might do). If such work was done though, it would be nice to read it.

And, as an aside, I should point that National Team plans is just one piece of the puzzle. An important piece, but just one piece. Plans for grass roots development, marketing and fundraising, for example, to the best of my knowledge haven’t been developed at all.

Time to Right the Ship

I think in this series I’ve made some fairly compelling arguments that call into question USA Team Handball’s National Team Plans. In the end, though, it’s really not about who’s right and who’s wrong. Nobody’s keeping score and we really all are on the same team.

But, in order to get everyone on the same page and rowing together I would suggest a couple of actions to right the ship:

- Develop a true strategic plan that clearly identifies some top level goals and objectives for USA Team Handball. Prioritize those goals and objectives, develop potential options for implementation, then evaluate and select those options for implementation. Develop those plans and options collectively using the USA Team Handball Staff, Board, Committees and anyone else in the USA Team Handball Community that wants to participate.

- Do 1) above transparently with the posting of strategic plans, board decisions on evaluation/selections and budget actions on the Federation website.

And it should be pointed that such fixes shouldn’t be too hard to implement. It’s acknowledged by many that we need a Strategic Plan, the committees are in place and that transparency is important. All USA Team Handball needs to do is finished what it started.