Note: This is part of an ongoing series, Charting a Way Forward for USA Team Handball (2019 Reboot): Link

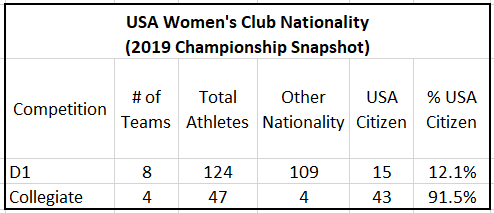

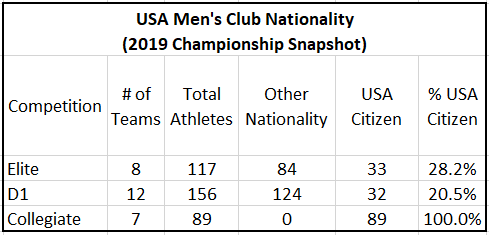

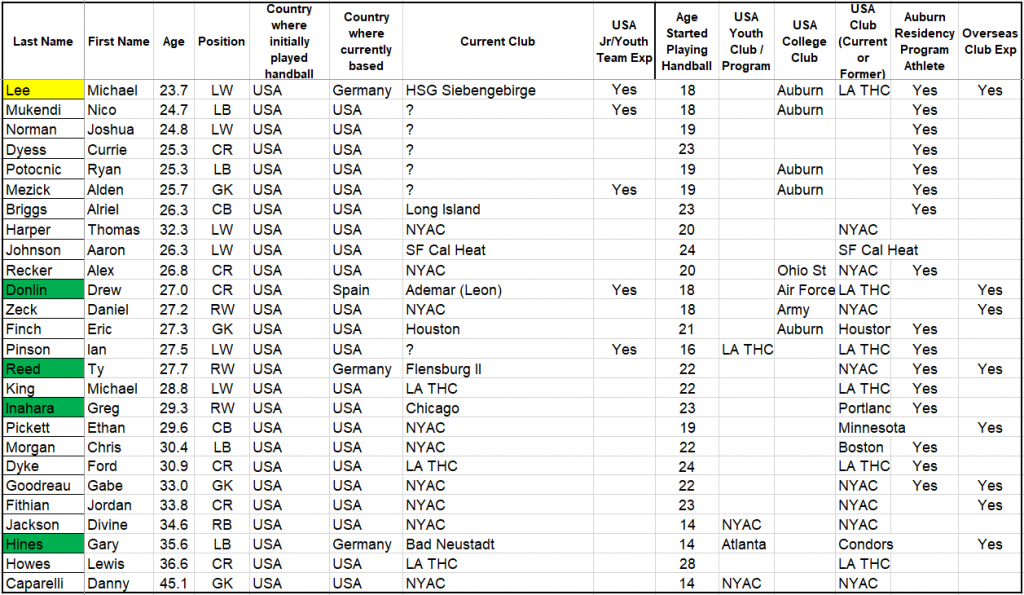

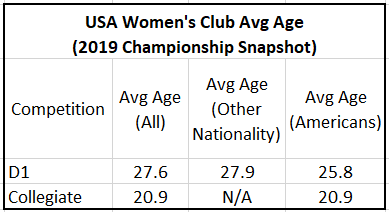

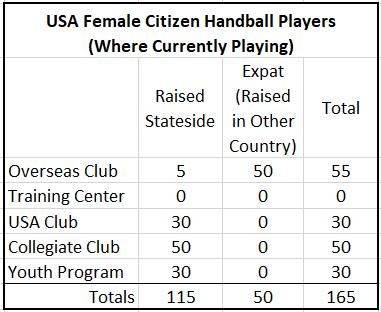

Parts 1, 2 and 3 provided an overview of Men’s and Women’s clubs in the U.S. It doesn’t take long to empirically determine that there aren’t very many clubs and that the few clubs we are for the most populated with expats. Here’s some context as to why this is so.

Starting a Club: Big Picture

It kind of goes without saying that all existing clubs at some point in the past had to get started. And, let’s make one thing clear up front. Starting a club is a huge undertaking. It takes organization skills. It takes resources (money). It takes time. (A lot of time) It takes determination. Either from one indefatigable person or a village willing to put in quite a bit of effort.

It is not easy when structures are in place to facilitate new clubs. It can seem like mission impossible when no such structures exist. For many people it might be the hardest thing they’ve ever tried to do.

It should therefore come as no surprise that many folks take initial steps to start a club, assess that it’s not going to be a walk in the park and fairly quickly decide to punt. That maybe they’ve got better things to do with their time and money. I used to kind of look down at those lazy talkers, but now older and wiser I sometimes think that maybe they’re the smart ones.

Back in 2013 I highlighted some of the challenges from my own experience in helping to start two clubs. With mixed success I might add. And, yes I must admit failure is not easy for someone who is used to succeeding at a lot of different things. As one gets older, however, one gets smarter and a little bit more humble.

Here are the major hurdles that typically have to be overcome on the way to starting a new club:

Hurdle 1) Recruiting Players

When you’re starting a new handball club, the first step is recruiting players. Anyone who has done this knows that it is not as simple as posting a flyer or a Facebook post and waiting for the players to simply show up. It might sort of work like that for a short window during the Summer Olympics every four years, but for the most part it involves working on your sales pitch. For some this is a simple task, but for others it requires really stepping out of their comfort zone.

Recruiting athletes is not easy and requires a lot of salesmanship. Adults in their 20s are busy starting a new career; perhaps in a significant committed relationship. They’ve got competing interests. A college student may be focused on their studies or simply happy playing pickup basketball or jogging as an outlet. Many people are simply not willing to make the time and money commitment to a club.

And, keep in mind this sort of convincing/recruiting can be challenging for a well-known sport that athletes are familiar with and have played before. Convincing/recruiting people to play a sport they are not familiar with or have never played before adds yet another layer of difficulty.

Yes, some folks, indeed, are interested in trying something new like handball. But, it’s a long path from checking out handball after you’ve seen it on TV to becoming fully committed to the sport. Typically, there’s a huge attrition rate as those new players discover that the sport is more physical and a whole lot harder to master than they thought it would be.

Thus, it should come as no surprise that U.S. clubs are heavily populated with expats. Yes, people seeking out… something they are familiar with and have played before vice seeking out an opportunity to join some other club to do something totally new. In a nutshell, this explains the predominance of Expat clubs in the U.S.

Hurdle 2) Achieving “Critical Mass”

Then there is the issue of “critical mass.” As in you really need around 16 athletes to have a truly viable club. Yes, a club can “get by” with fewer athletes. Heck, the mighty Condors once took 3rd place at open Nationals with just 7 athletes and one of them wasn’t really a goalie! (Iron Man Handball at its finest.) But, generally you want enough athletes to scrimmage at practices, for substitution in matches and to handle the natural attrition that occurs due to injuries and other commitments.

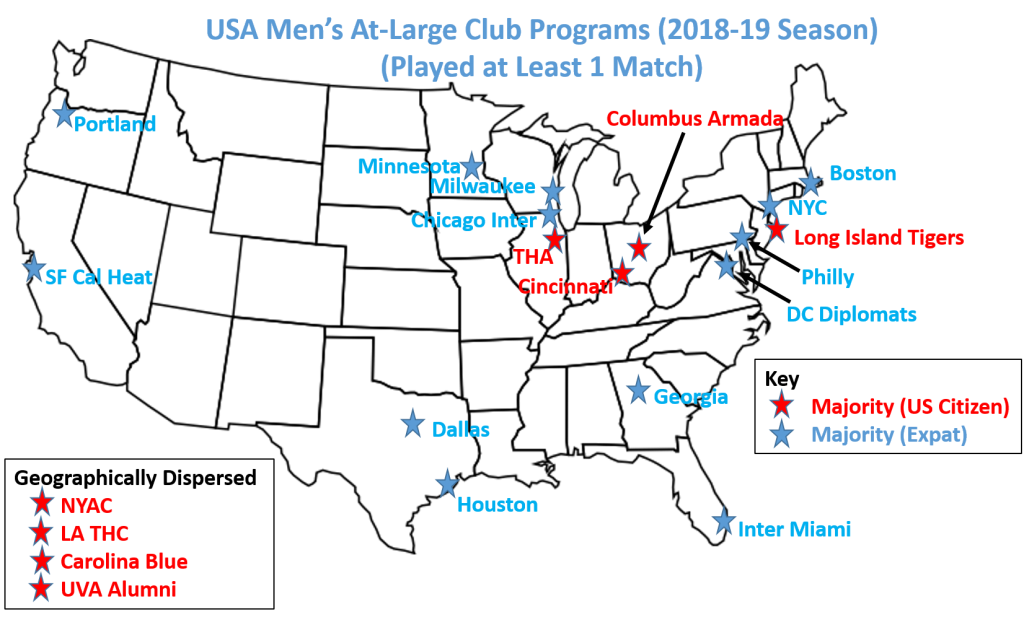

It goes without saying that achieving such critical mass is much easier in big cities. Big cities, where, you guessed it, there’s a healthy supply of handball loving expats moving in and out every year. The bigger the city, the easier such recruitment is. It should come as no surprise, for instance, that one of the largest and most international cities in the world, New York City, has such a strong and vibrant club.

Achieving critical mass in smaller population areas can also be done. It’s just that it’s much harder and requires really strong commitment. And, effective recruitment of stateside Americans to make up for the shortage of expat players available. So, a new club is always on the lookout for new athletes to get to the critical mass needed to practice.

Hurdle 3) A Place to Practice and Equipment (Balls and Goals)

Once you’ve got enough players it’s then possible to actually practice. But, of course, one can’t really practice without a gym, balls and goals. For the most part, this is a logistical hurdle that can be solved pretty easily with money. Balls and goals can be purchased or in the case of goals, built. Sometimes, USA Team Handball or some other organization can even come through with a donation. A gym to practice in can be a little more tricky. Depending on where the club is being started there may well be issues with finding a gym that’s big enough for a handball court and that can rented for practice at a reasonable cost. And, finding a gym that will allow stickum is also becoming tougher as well.

Which leads to another point: cost. Athletes brand new to a sport are often reluctant to contribute to the logistical overhead associated with a club. This inevitably means that the fully committed have to front a lot of these costs. This can be problematic depending on the number of people willing to contribute, as well as the financial situation of those people. For the most part, wherever there’s a new club starting up, it’s a pretty safe to assume that somebody is paying out of pocket to make it happen.

Hurdle 4) Finding Opponents to Play

This hurdle is sometimes forgotten, but in the big picture of things has to be considered. The U.S. is a huge country and some clubs have better “geography” than others. For the most part this means not being “too far” from other clubs. Ideally, being able to drive to competition that is less than 5 hours away. Beyond that distance generally requires flying for competition and finding enough athletes willing to do that can be really challenging for a new club.

Changing the Sequence of Club Organization

I’m sure some reading this have mentally noted that the order of these hurdles can be altered. In particular, finding a gym to practice (Hurdle) 3 can be moved up. This, however, is a risky venture because it’s not yet certain that the players needed will indeed get successfully recruited. (You, don’t want 5 people playing catch in an empty gym you’ve rented out.) And, this creates a bit of an awkward chicken and egg situation. As in, you need players to practice, but you also need a gym and equipment for those players to practice.

Insurmountable Hurdles?

Finally, would be organizers have to also take a hard, critical overview of the overall situation. Are there just too many hurdles? Or, is one hurdle simply too high? The answer to these questions is sometimes yes. I know people like to think that “if there is a will, there is a way” and I guess that’s true to a certain extent. I mean some dynamic handball loving guy in Nome, Alaska could put his heart and soul into establishing a handball team there, but there would be some serious mountains to climb. No handball expats, limited population base and a flight to Vancouver or Seattle just to play some matches. It is theoretically possible that it could be done, it’s just not very unlikely.

A Current Example: Detroit Handball

I’ve been around a while and I’ve seen quite a few clubs come and go, and even come back. And, one can generally look at the location and the people behind the effort and assess what their likelihood of success.

Recently, Joey Williams, has taken on the task of starting a new club in Detroit, Michigan. Joey has been a goalie on the Jr National Team and is pretty high on the “passionate scale” when it comes to handball, having attended a goalie camp in Croatia and trained in Denmark on his own dime.

As I highlighted at the beginning of this article it generally takes someone pretty committed to take on the effort of starting a club and Joey is nearly off the charts in that department. Failure in this instance won’t be for lack of trying.

In terms of recruitment he’s been very active and has been using social media effectively. He’s done an Instagram Takeover of the USA Team Handball Instagram account and recently posted a short infomercial on the new club. “Critical Mass” has not been achieved yet, but generally that takes time.

Depending on how one defines the Detroit metropolitan area there is between 3.7M to 5.3M so that’s quite a few people to draw from. According to this list of metropolitan areas, Detroit is the 11 largest metro area in the U.S. (And, no surprise here: you’ll see quite the correlation between U.S. Handball club locations and the top end of this population ranking.) In fact, one might wonder why there hasn’t been a club effort in Detroit sooner. It’s hard to say for sure, but I would speculate that the economic downturn probably has something to do with it. And, in turn, I’m guessing that has resulted in fewer young expats with a handball background finding their way to the Motor City. Not to say there aren’t some there just that it might be fewer than other cities which are perceived as hipper.

In terms of geography and distance to other clubs Detroit is in pretty good shape. Chicago, Pittsburgh and Columbus, Ohio are within 5 hours drive. And, maybe the development of a Detroit club will spur development of a club program at the University of Michigan so that the Ohio St – Michigan rivalry can be extended to Team Handball.

In terms of logistics, there are a number of suitable gyms, although they are still looking for one that will allow stickum. And, the capital outlay necessary for balls and goals is still needed.

Taking into account all of these factors, I would put the likelihood of a club successfully being established in Detroit as fairly high, but with one huge caveat. And, that caveat is that everything seems to be pretty much revolving around one highly dedicated guy. If Joey can’t continue to fully dedicate himself to the effort or has to move somewhere else there isn’t enough of a club established yet to sustain what’s been started.

This is nothing new. In just about every instance of a club being established it has been due to the efforts of a few key (or even just one) individual. And, the same is true in regards to the folding of most clubs. Generally they have folded due to the departure of a few (or even just one) key individual. The clubs that stick around in most cases have been the ones that create a “village” of dedicated individuals that share the load.

If you want to help Joey Williams and the Detroit Handball Club they’ve set up a crowdfunding site. Check out that link and others below.

Detroit Handball Club

– Crowdfunding Site: Link

– Website: Link

– Facebook: Link

– Instagram: Link